Outsourcing Everyday Jobs to Thousands of Transient Functional Containers

micahlerner.com

From Laptop to Lambda: Outsourcing Everyday Jobs to Thousands of Transient Functional Containers

Published July 24, 2021

Found something wrong? Submit a pull request!

This week’s paper review is the second in a series on “The Future of the Shell” (Part 1, a paper about possible ways to innovate in the shell is here). As always, feel free to reach out on Twitter with feedback or suggestions about papers to read! These weekly paper reviews can also be delivered weekly to your inbox.

From Laptop to Lambda: Outsourcing Everyday Jobs to Thousands of Transient Functional Containers

This week’s paper discusses gg, a system designed to parallelize commands initiated from a developer desktop using cloud functions - an alternative summary is that gg allows a developer to, for a limited time period, “rent a supercomputer in the cloud”.

While parallelizing computation using cloud functions is not a new idea on its own, gg focuses specifically on leveraging affordable cloud compute functions to speed up applications not natively designed for the cloud, like make-based build systems (common in open source projects), unit tests, and video processing pipelines.

What are the paper’s contributions?

The paper’s contains two primary contributions: the design and implementation of gg (a general system for parallelizing command line operations using a computation graph executed with cloud functions) and the application of gg to several domains (including unit testing, software compilation, and object recognition).

To accomplish the goals of gg, the authors needed to overcome three challenges: managing software dependencies for the applications running in the cloud, limiting round trips from the developer’s workstation to the cloud (which can be incurred if the developer’s workstation coordinates cloud executions), and making use of cloud functions themselves.

To understand the paper’s solutions to these problems, it is helpful to have context on several areas of related work:

- Process migration and outsourcing: gg aims to outsource computation from the developer’s workstation to remote nodes. Existing systems like distcc and icecc use remote resources to speed up builds, but often require long-lived compute resources, potentially making them more expensive to use. In contrast, gg uses cloud computing functions that can be paid for at the second or millisecond level.

- Container orchestration systems: gg runs computation in cloud functions (effectively containers in the cloud). Existing container systems, like Kubernetes or Docker Swarm, focus on the actual scheduling and execution of tasks, but don’t necessarily concern themselves with executing dynamic computation graphs - for example, if Task B’s inputs are the output of Task A, how can we make the execution of Task A fault tolerant and/or memoized.

- Workflow systems: gg transforms an application into small steps that can be executed in parallel. Existing systems following a similar model (like Spark) need to be be programmed for specific tasks, and are not designed for “everyday” applications that a user would spawn from the command line. While Spark can call system binaries, the binary is generally installed on all nodes, where each node is long-lived. In contast, gg strives to provide the minimal dependencies and data required by a specific step - the goal of limiting dependencies also translates into lower overhead for computation, as less data needs to be transferred before a step can execute. Lastly, systems like Spark are accessed through language bindings, whereas gg aims to be language agnostic.

- Burst-parallel cloud functions: gg aims to be a higher-level and more general system for running short-lived cloud functions than existing approaches - the paper cites PyWren and ExCamera as two systems that implement specific functions using cloud components (a MapReduce-like framework and video encoding, respectively). In contrast, gg aims to provide, “common services for dependency management, straggler mitigation, and scheduling.”

- Build tools: gg aims to speed up multiple types of applications through parallelization in the cloud. One of those applications, compiling software, is addressed by systems like Bazel, Pants, and Buck. These newer tools are helpful for speeding up builds by parallelizing and incrementalizing operations, but developers will likely not be able to use advanced features of the aforementioned systems unless they rework their existing build.

Now that we understand more about the goals of gg, let’s jump into the system’s design and implementation.

Design and implementation of gg

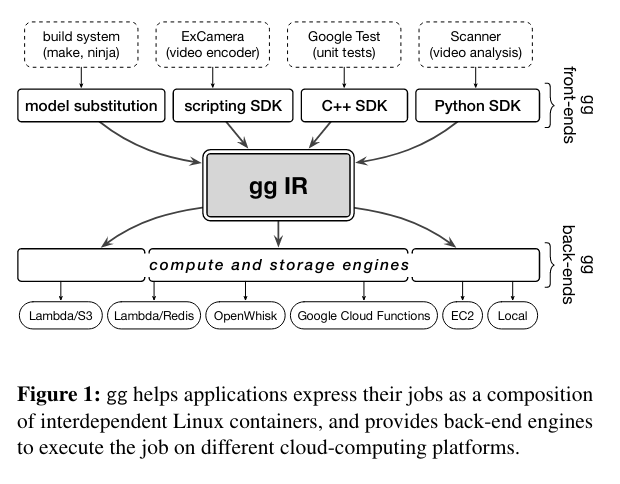

gg comprises three main components:

- The gg Intermediate Representation (gg IR) used to represent the units of computation involved in an application - gg IR looks like a graph, where dependencies between steps are the edges and the units of computation/data are the nodes.

- Frontends, which take an application and generate the intermediate representation of the program.

- Backends, which execute the gg IR, store results, and coalesce them when producing output.

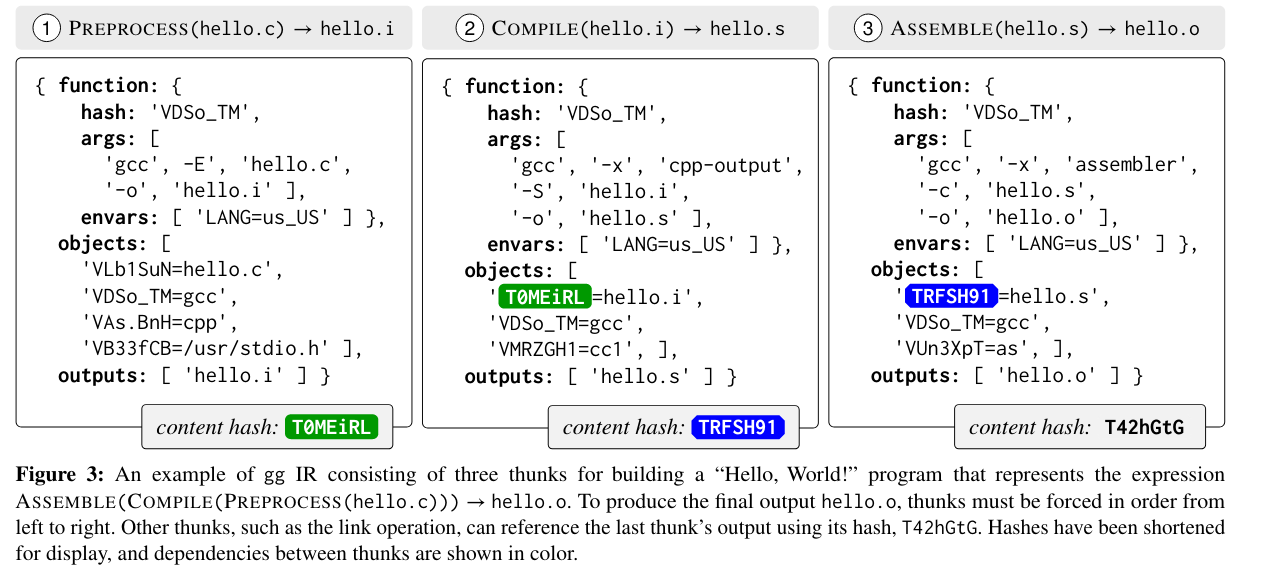

The gg Intermediate Representation (gg IR) describes the steps involved in a given execution of an application. Each step is described as a thunk, and includes the command that the step invokes, environment variables, the arguments to that command, and all inputs. Thunks can also be used to represent primitive values that don’t need to be evaluated - for example, binary files like gcc need to be used in the execution of a thunk, but do not need to be executed. A thunk is identified using a content-addressing scheme that allows one thunk to depend on another (by specifying the objects array as described in the figure below).

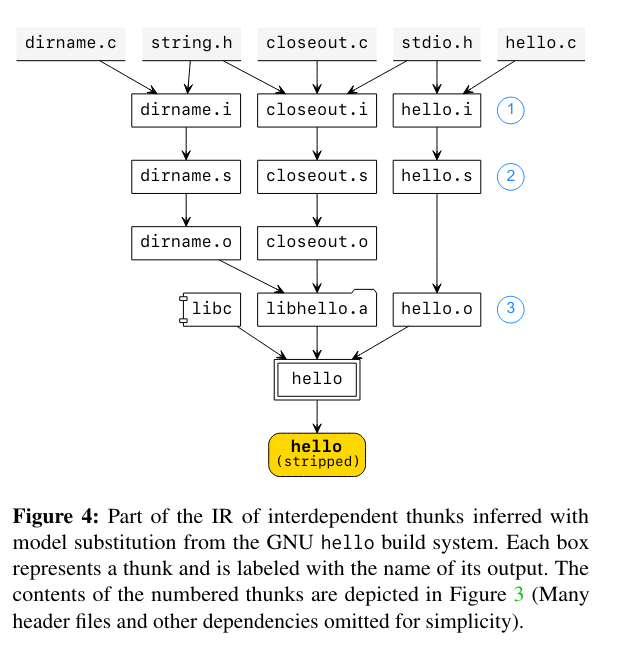

Frontends produce the gg IR, either through a language-specific SDK (where a developer describes an application’s execution in code) or with a model substitution primitive. The model substitution primitive mode uses gg infer to generate all of the thunks (a.k.a. steps) that would be involved in the execution of the original command. This command executes based on advanced knowledge of how to model specific types of systems - as an example, imagine defining a way to process projects that use make. In this case, gg infer is capable of converting the aforementioned make command into a set of thunks that will compile independent C++ files in parallel, coalescing the results to produce the intended binary - see the figure below for a visual representation.

Backends execute the gg IR produced by the Frontends by “forcing” the execution of the thunk that corresponds to the output of the application’s execution. The computation graph is then traced backwards along the edges that lead to the final output. Backends can be implemented on different cloud providers, or even use the developer’s local machine. While the internals of the backends may differ, each backend must have three high-level components:

- Storage engine: used to perform CRUD operations for content-addressable outputs (for example, storing the result of a thunk’s execution).

- Execution engine: a function that actually performs the execution of a thunk, abstracting away actual execution. It must support, “a simple abstraction: a function that receives a thunk as the input and returns the hashes of its output objects (which can be either values or thunks)”. Examples of execution engines are “a local multicore machine, a cluster of remote VMs, AWS Lambda, Google Cloud Functions, and IBM Cloud Functions (OpenWhisk)”.

- Coordinator: The coordinator is a process that orchestrates the execution of a gg IR by communicating with one or more execution engines and the storage engine. It provides higher level services like making scheduling decisions, memoizing thunk execution (not rerunning a thunk unnecessarily), rerunning thunks if they fail, and straggler mitigation.

Applying and evaluating gg

The gg system was applied to, and evaluated against, four use cases: software compilation, unit testing, video encoding, and object recognition.

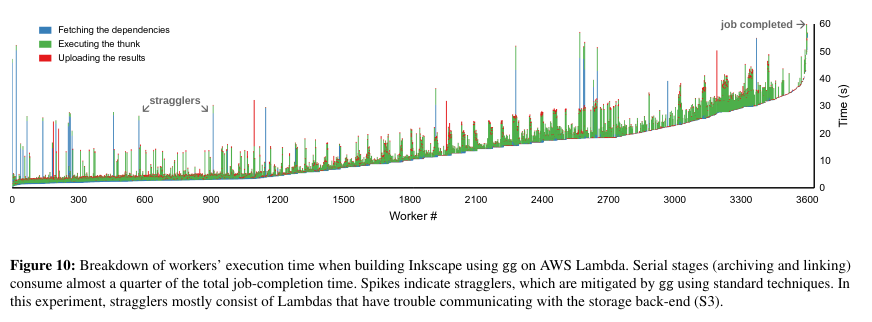

For software compilation, FFmpeg, GIMP, Inkscape, and Chromium were compiled either locally, using a distributed build tool (icecc), or with gg. For medium-to-large programs, (Inkscape and Chromium), gg performed better than the alternatives with an AWS Lambda execution engine, likely because it is better able to handle high degrees of parallelism - a gg based compilation is able to perform all steps remotely, whereas the two other systems perform bottlenecking-steps at the root node. The paper also includes an interesting graphic outlining the behavior of gg worker’s during compilation, which contains an interesting visual of straggler mitigation (see below).

For unit testing, the LibVPX test suite was built in parallel with gg on AWS Lambda, and compared with a build box - the time differences between the two strategies was small, but that authors argue that the gg based solution was able to provide results earlier because of its parallelism.

For video encoding, gg performed worse than an optimized implementation (based on ExCamera), although the gg based system introduces memoization and fault tolerance.

For object recognition, gg was compared to Scanner, and observed significant speedups that the authors attribute to gg’s scheduling algorithm and removing abstraction in Scanner’s design.

Conclusion

While gg seems like an exciting system for scaling command line applications, it may not be the best fit for every project (as indicated by the experimental results) - in particular, gg seems well positioned to speed up traditional make-based builds without requiring a large-scale migration. The paper authors also note limitations of the system, like gg’s incompatibility with GPU programs - my previous paper review on Ray seems relevant to adapting gg in the future.

A quote that I particularly enjoyed from the paper’s conclusion was this:

As a computing substrate, we suspect cloud functions are in a similar position to Graphics Processing Units in the 2000s. At the time, GPUs were designed solely for 3D graphics, but the community gradually recognized that they had become programmable enough to execute some parallel algorithms unrelated to graphics. Over time, this “general-purpose GPU” (GPGPU) movement created systems-support technologies and became a major use of GPUs, especially for physical simulations and deep neural networks. Cloud functions may tell a similar story. Although intended for asynchronous microservices, we believe that with sufficient effort by this community the same infrastructure is capable of broad and exciting new applications. Just as GPGPU computing did a decade ago, nontraditional “serverless” computing may have far-reaching effects.

Thanks for reading, and feel free to reach out with feedback on Twitter - until next time!

Comments

Post a Comment